I came to know Ming Ren and his work only a little over a year ago when I moved to San Francisco. But once we met, I feel I had known him all along, in a fundamental way. That is because his art demonstrates a life-long, and still ongoing, exploration and negotiation of artistic languages of China and the West, a topic that interests me deeply. Even though Ming Ren’s artistic development may be classified, in an art historical sense, into phases of transformation, or “reincarnations,” there is always the common thread: a determined pursuit to integrate the artistic legacy of his birth country and that of his adopted home, and to create a form of art that is uniquely his. Shuttling back and forth between US and China as both an artist and an art educator, Ming Ren is exerting a tangible influence on the artistic dialogue and trajectory in both places.

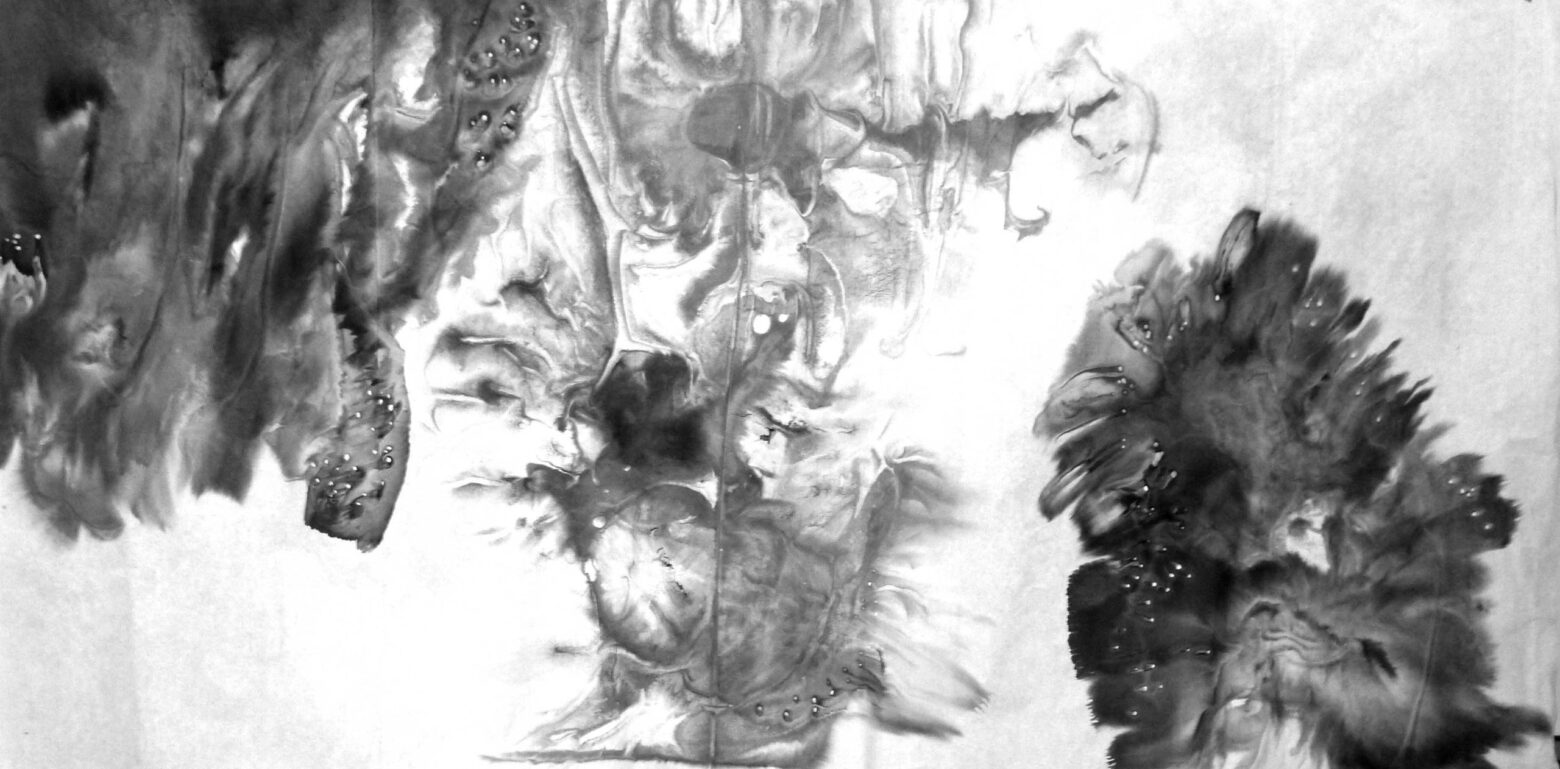

Looking specifically at Ming Ren’s works published in the present volume, we may see that the works, whether monumental or intimate in scale, manifest a confident, self-assured spirit through the use of bold splashes of strong colors that fill out almost the entire picture plane and build up texture, forms, and depth. Such daring splashes are at once calculated and spontaneous, attaining a quality that I would like to call “controlled freedom”. The powerful splashes are often tempered with a pronounced linear quality expressed through either brushlines, or creases in the paper, or streaks of ink or colors naturally formed in the process of painting. This linear quality harks directly back to the fountain head of Chinese calligraphy, the most venerable art form in China, and an art form of which the supreme accomplishment is none other than individualistic expression within a set of prescribed restrictions, or in other words, “controlled freedom”. The bold splashes and rhythmic calligraphic strokes give Ming Ren’s painting a gestural quality and powerful composition that recall traditional “ink play” favored by Chinese literati as an ultimate means of self-expression and also demonstrate influence of American action painters of the Abstract Expressionism. Yet, emerging from this synthesis of Eastern and Western aesthetic values is the irrepressible Ming Ren himself.

Ming Ren evidently seeks other dialogues in his art. Reading his paintings with their titles in mind, such titles as “Night at Moon,” “My World of Universe,” “The Melody of Prosperity,” “Blue Symphony,” we can detect at least three subjects that Ming Ren engages in his art: space (cosmology), time (linear continuum), and sound (music). His work seems able to express a sense of temporal immediacy, as if at a moment the starry light breaks through the opacity and paints the world with delight, energy, and colors, as if the splashes and lines are melodic notes and symphonic tunes gushing forth tone poems. In this way, Ming Ren’s paintings are both abstract and narrative, and marked with an emphasis on the interactions between shapes (space) and tonal appearance (time and sound). Those commingling qualities entail different levels of comprehending Ming Ren’s paintings, creating a visual interest that challenges any particular eastern or western sensibilities. To this particular reader, it is the intention to transcend the differences between East and West, as well as his previous works, that gives this new body of works a special mark in Ming Ren’s career.

Jay Xu

Director, San Francisco Asian Art Museum

November, 2009