“Fire and water have qi but do not have life. Grasses and trees have life but do not have perceptivity. Fowl and beasts have perceptivity but do not have yi (sense of right and wrong, duty, justice). Men have qi, life, perceptivity, and yi.”

Confucian philosopher, Xun Zi (313BC-238BC)

Each artist decides for himself or herself what particular form of making will best give shape to the meaning they wish to convey. An artist discovers the materials they have an affinity for and marries the processing of those materials with their conceptual message. Through their work their chosen combination of making and reflecting becomes their distinctive contribution to the world. But is it that simple? What conspires to shape those choices? What is the relationship between conscious decision and other forces that interact to give form to the work?

In the case of the work of Ren Ming these questions are particularly relevant. He is a master of his chosen craft, working with pigment and ink on paper. However, the means by which he has chosen to work also gives these materials a great voice in the ultimate form of the work.

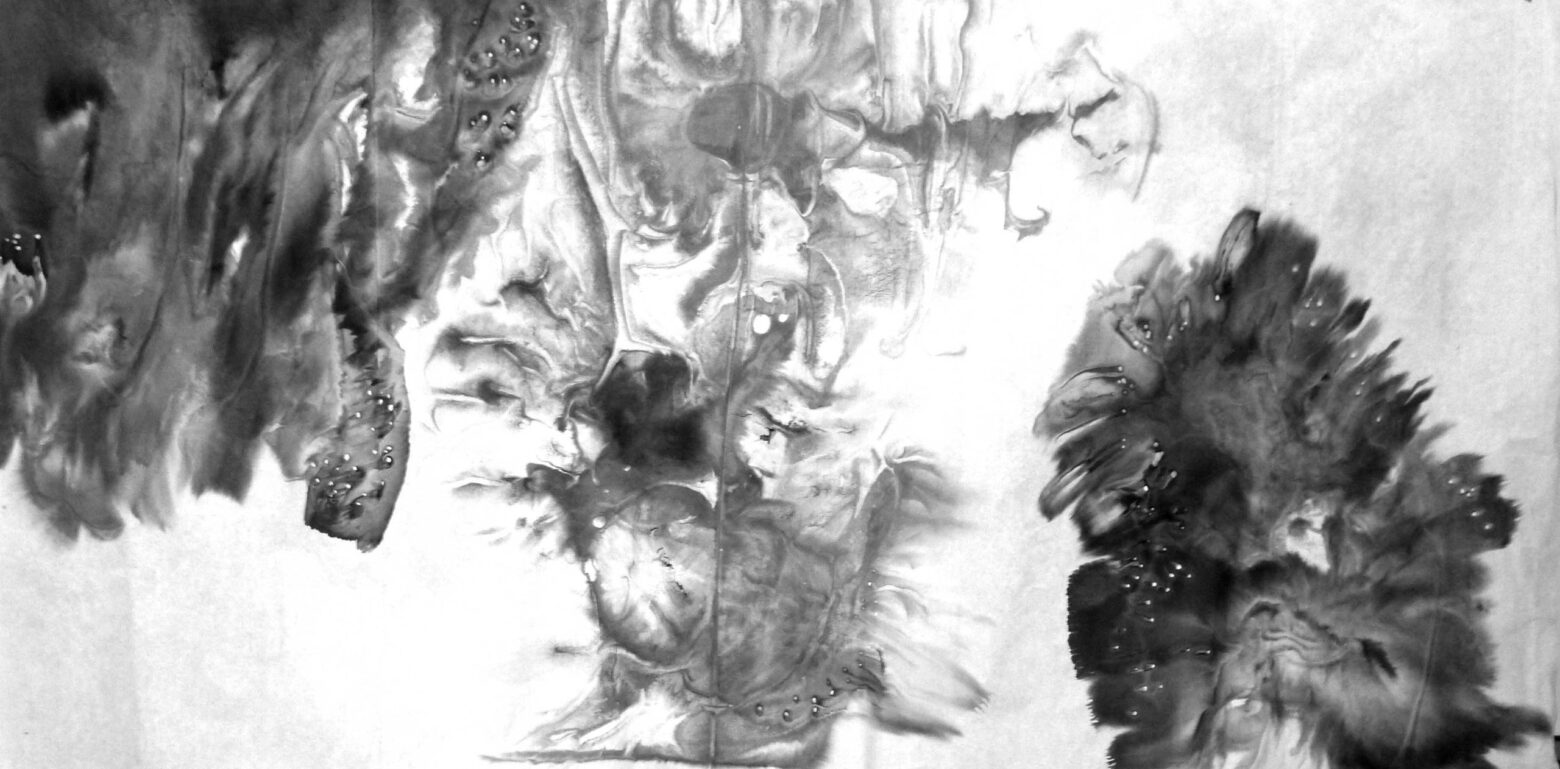

Ren Ming’s work is subtle in how it involves will and acquiescence. As he applies his wet media to the paper, the paper responds drawing in the pigmented liquid and gradually fixing tones and colors in place. In other areas it sits on the surface and can be moved with brush and breath bringing about transformative landscapes that hover between inner and outer space. He plays with traditions of Chinese brush painting coaxing an almost imperceptible sense of human intervention. His balance of delicate and disruptive forms appears to have been laid down by nature more than by man.

Ming’s mixture of media create a world that might be seen from the Hubble Telescope giving a glimpse of volatile forces from long ago that are galactic in scale. At the same time one can also see his work as portraying the minute forces seen in the Petri dish in the biologist’s lab. The mixture of media stirs up the imagination as he stirs up the primordial forces of nature’s palette in the rich coloration of his work.

Perhaps Ming has arrived at this unique recipe for the creation of his work because of his shuttling between his homeland China and the United States. Constantly in flux he traverses these cultures with the ease of the artist comfortable with adjusting his chosen language of creation to these influences. He has been immersed with Eastern traditions and equally with Western ones. The influence of Guo Xi or Wang Hui is just as powerful seen in Ming’s work as that of Jackson Pollock or Helen Frankenthaler.

In no other cultural tradition has nature played a more important role in the arts than in that of China. And conversely, in American art the role of nature has been gradually more subservient to that of the world of man’s creations and a focus on introspection for inspiration. Since the earliest dynastic periods the Chinese imagination has developed their art through the study of nature. The importance of nature in art, poetry and philosophy is often a result of its value as a symbol of vital energy, qi.

One might debate whether qi exists as a force separate from matter, or arises from matter, or whether matter arises from qi. In some sense Ming’s work becomes the field for contemplating these questions about role of nature or man as the agent of this life force.

Ming’s work creates a contemporary locus for the continuum of critical dialogue with the past in Chinese art and philosophy. The choice of his particular style immediately links his work to the personalities and ideals of earlier painters. And yet his chosen style becomes a language by which to convey his specific beliefs. Engaging with Ming’s work continues that tradition of intimate experience. The act of unrolling a scroll painting by Ming provides a further, physical connection to the work. It is through such interactions with his art that meaning is gradually revealed. It is such in interactions between art and viewers that profound questions are contemplated. These probing moments have been and will continue to be repeated over the centuries permitting deeper, more timeless meanings to accrue.

Early Chinese texts contain sophisticated conceptions of the natural world and of the cosmos. Through their work artists of earlier times, like now, gave visualization to those linguistic concepts. Ideas about the nature of being are part of the foundation of Chinese culture, and were incorporated into the fundamental tenets of Daoism and Confucianism. These two philosophies along with Buddhism, somewhat later, contribute to the notion of nature as self-generating through complex natural elements continuously changing and interacting.

Much like this early belief system the work of Ren Ming brings to life this philosophy in the process he employs as an artist. He initiates a complex swirl of liquid and matter and coaxes it into a flow of watery rhythms. He assists the pigments and inks to coalesce from their beginning as disparate elements into a unified world under his masterful artistic influence.

Dao may be a dominant principle by which all things exist, but it is not understood as a causal or governing force. Just as Chinese philosophy tends to focus on the relationships between the various elements in nature rather than on what makes or controls them so to does the focus of Ren Ming’s work. It has come into being through not force but through yielding to the movement of liquids and pigments in the yin and yang of creating his visual world.

Within the structure of Ming’s work one can see the dark, the secretive, the cool in active relationship to the bright, the revealed and the hot. These complementary relationships are manifest in the color and in the interplay of intensive moments against quiet expanses of space. The work alternates between a depth of space that seems almost infinite and the close up impression of forms a short distance from one’s eye. As these aspects of the work constantly interact it forces the viewer to shift from one extreme to the other, giving rise to the sense that the nature of Ming’s work is one of unending change.

The reference to nature and landscape is unavoidable in Ren Ming’s work. Typically forms resemble mountain peaks and valleys, rivers and oceans, clouds and skies as well as more extraterrestrial images of deep space. But, as coherent spaces begin to form they are quickly perforated or concealed amid new clefts that open up to emit obscuring vapors that turn the world inside out. There is no axis, no fixed horizon in Ming’s cosmos.

In the world of Ming’s work, the life force, or qi, finds a place for contesting those phenomena that gave rise to the cosmos and that are essential to being. Ren Ming’s landscape painting has evolved into a genre that embodies the universal longing of civilized people to escape their quotidian world to commune with nature and with larger realms of thought and space. Through his singular landscapes he continues and at the same time disrupts a tradition in Chinese art has gone on for millennia and has found a new and inspiring attributes in his contemporary artistic idiom.

Jay Coogan

President, Minneapolis College of Art and Design

November, 2009