In every artist there’s a solid streak of sheer bravery. My friend the painter Ming Ren has it. Going into the studio to make work on an heroic scale, struggling to overcome the reluctance of paint and materials to do his bidding, fighting to create the right balance between the ideas in the work and the ways of making that bring them to life. And as with most painters, doing this alone. Nothing between him and the work, which stands or falls by his hand alone, in an intense personal and intimate dialogue with ideas and materials. And working on a such large scale requires an unusual amount of planning, to deal with the sheer physicality of production. All challenges and risks are magnified. I have great admiration for artists who take on these challenges. In his studio there must be days of great joy and also days of great frustration, when nothing goes right – days when the paint wins, and days when the fortitude and stamina of the artist overcome the struggle and Ming Ren’s beautiful haunting works are the result. But as many artists at the end of an exhausting day will tell you – “this painting business is like unarmed combat, you’ve got to be brave”.

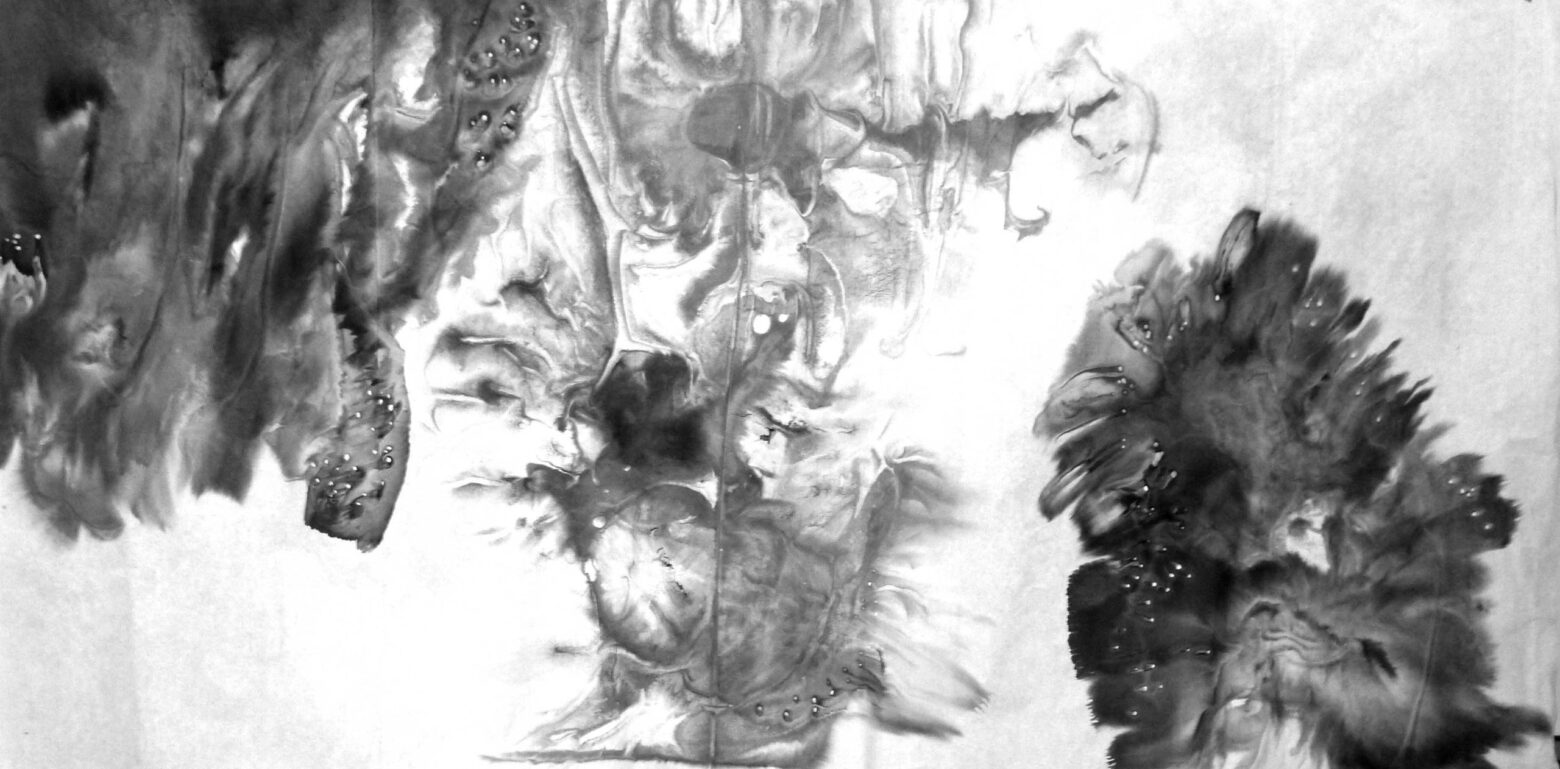

Ming Ren has entitled a new body of work his “Perspective on a New Universe”, and it continues a theme that plays with macro and micro scales. An exceptionally powerful example is the large-scale “Snowing Moon”, in which the artist plays with contrasts, a signature constant in his work. The overall effect is like looking at the astronomical photographs from the Hubble Space Telescope, gaseous clouds of paint are counterpointed with carefully-placed white ‘distant stars’. Thus the whole effect is of the untouchable cosmic vastness, but the surface has the appearance of something far more earthly and common and everyday, like windowpanes covered with a thick frost.

By reducing the color range of the work to subtle monochromatics with slight tints of sepia and pale blue, that ‘ethereal’ quality of cosmic reference plays against that ‘local’ reference. The surface is built up through successive layers of staining, creating translucent veils under which older banks of clouds and mists are seen or just suggested.

Such a way of making is again a set of counterpoints, with the artist setting the parameters and the context (often a grid of vertical rectangles), but allowing the paint to have a life of its own with in the confines – inevitably leading to multiple unpredictable or even uncontrolled effects. And there is something about these works that every viewer responds to – they are simply gorgeous, just simply beautiful.

What do these extraordinary works remind you of ? Well, standing before a vast Ming Ren painting, many references come to the mind and eye. Cosmic phenomenon, patterns in cracking ice, the subtle swirls of great watercolor washes, the shimmer of Fortuny silks, reflections in rich glossy lacquerware, Japanese and Chinese screens, the dash and drama of American and European Abstract Expressionist and taschiste painting, the Asian calligraphic tradition of sumi-e painting with rich ink on lovely paper, and the abiding elegant overtones of classical Chinese landscape painting and recollections of Chinese murals. But the synthesis of all these references is Ming Ren’s alone. Like a composer and conductor his highly original vision brings together unlikely and very disparate elements, making them into a great chorus of many voices, united.

He’s not at all perturbed by this ‘partnership’ between the imaginative artist and inanimate materials, and has spoken with enthusiasm about the “happy accidents” that occur. There is a sense of wonder and magic in the intensity with which Ming Ren manipulates the materials – in an extended conversation I had with him he talked about the joy of those “Wow !” moments when the controlled effects of staining and brushing coalesce into unexpected results – “These effects that occur in colour, pattern, texture, tones, lines, brightness and darkness – they fascinate and excite me, and truly I see them as discoveries that I have enabled. Some are perspectives that are about small details, some about much larger dynamic movements within the paintings”. His respect for allowing the characteristics of the materials with which he works to play a major role is distilled in a wonderful phrase Ming Ren uses – they are “magic happenings in the universe I have created”.

These “magic happenings” result in work that has an emotional resonance combined with the physical impact that comes from standing in front of works that are over 8 feet high and 16 feet wide. They envelope one. The viewer’s eyes are filled from edge to edge, and it is no surprise that many visitors to exhibitions that contain “Night at Moon” (8 feet square) and “Snowing Moon” (8 feet x 16 feet) or “Blue Symphony” (4 feet x 12 feet) are “stunned”, and report that they find the works “dream-like”, and that they “sing”, are “atmospheric” and “inspirational” . Traditional Chinese landscape painting was always about such responses, and was always rooted in nature. The idea was simple but profound – how communicating not the ‘surface’ but the deeper spirituality seen through the art improved the soul, enhancing the values and quality of human life. Ming uses such sensational words himself when commenting on how his work has progressed since his previous major exhibition: “I’ve learned that I am discovering more and more what we cannot actually see with our eyes alone, but rather what we can only ‘dream’ and ‘feel’ with our imagination. I like this increasingly unpredictable way of working … each work is unique, I can’t duplicate these ‘accidental’ effects. Because I’ve chosen to work with a mixture of mediums I combine acrylic with self-made materials, each work has some surprises in store for me”.

The largest new works are a challenge in many ways, with many risks, and many surprises. The vast surface is not a traditional stretched canvas, but Chinese shuan paper (or xuan paper), a heavy traditional material made from woven plant materials. In Chinese tradition and symbolism, this specific paper is renowned for its high quality, and was reserved for use only by the most gifted and accomplished artists and calligraphers. Ming Ren pastes this paper flat onto a canvas, which is then stretched onto a wooden support framework. The painting materials are careful chosen for their ability to interact with the fiber of the paper, which is notable for its ability to carry both the lightest of stains and heavy paint. The choice of shuan paper is important – symbolically it is a bow of deep respect to the ‘partnership’ that will develop between the prepared surface and the materials that will be placed upon it. The materials themselves are a mixture of Chinese, Western and amalgamations the artist has invented. Thus the paper has to be able to absorb water-based pigments of many kinds – Ming Ren uses Chinese calligraphers inks, opaque egg-tempera (also known as gouache or poster-color), liquid acrylics, dry pigments, watercolor and textile inks. His mastery of such diverse mediums gives him the confidence to experiment with their chemical composition – adding salt, milk, and even detergents to make new materials. All this demonstrates how carefully he assembles the parts, with painstaking research, but then makes lively counterpoints and contrast in the spontaneity of gesture and mark-making as the work develops over this well-prepared ground.

But the artist carefully controls the final appearance of the work, overlaying with glazes of different densities, and applying matt and gloss finishes to create contrasts across the surface. But of course it’s not about the surface – Ming’s work is completely in harmony with the words of the Tao te Ching “He who is truly great does not dwell upon the surface, but what it stands for, and what lies beneath it”. Nevertheless, as a person fascinated by how a painter ‘engineers’ a work, assembling the materials, and directing the process of realization, I am considerably in awe of the combined physical power and elegance in Ming Ren’s work.

These works are compositions that show a highly intelligent artist at work, and whose works become stronger and richer as they evolve. He is very aware that each new body of works steps beyond the achievements of the previous exhibition, which he sees as an organic process, fed by travel, extended conversation with curators, critics, fellow-artists, visits to galleries and museums. A man of considerable and restless energy, one may think of his interests as being scattered and perhaps not focused. Not so. Especially notable in Ming Ren’s work is that his journey as an artist is well-defined, and that there are always two constant companions : the first is his kaleidoscopic interests in everything in the world, as already noted. The second is that he never forgets his Chinese heritage. But how he came to make the works he makes now is the remarkable story of the maturation of this artist’s vision, and his absolute dedication to that vision. From his early training as an artist whose work was intended to be state-supported illustrational painting in the style of Russian Cold War propaganda art, Ming Ren made an extraordinary conversion to a highly personal idea of his own art. After successful study at the famous China Academy of Art, where his study of oil painting (an uniquely Western method of art-making) was complemented by study of the uniquely Chinese ways of calligraphy and traditional landscape painting. He received a Master of Fine Art degree from the San Francisco Art Institute (1991), and has been teaching in the US, for example at Rhode Island School of Design. The opportunity to be on both coasts of America gave him not only interaction with the teaching faculty of these colleges, but visits to their deep library holdings, conversation with fellow painting students who had been brought up with a very different history of art, and, perhaps most importantly, direct observation of the best examples of post World War II American and European painting in the museums of Boston, New York and California. His absorption of the traditions

of non-objective painting history in the West, and his highly-creative experiments with new materials moved his work far from narrative paintings to work that might be ‘about’ a subject, but a subject that was implied rather than illustrated. Released from ‘the tyranny of literal depiction’, he began making work that was akin to music in its lyricism and ability to create an emotional response, though visually (“Blue Symphonic Sand”, 2002). Equally, landscape and forms derived from anonymous rocks, strata and specific places were referenced in the titles he chose (“Red Desert” and “Gobi Desert”, 2001, “Warm Wind from Shimalaya”, 2003). In these works there are strong suggestions of the vertical scroll compositions of historic Chinese artists, but in them and in works like “My Dream of Ink”, 2001, there is a sensibility informed by Western traditions. The sheer joy of play with materials is evident, and Ming Ren clearly celebrates the versatility of paints and inks in virtuoso works. The ying of the paint, in balance with the yang of the canvas and paper.

While his work is new and dramatically original in conception and execution, Ming Ren honors the traditions of Chinese art-making in his own and completely contemporary works. His work extends and enriches the ancient xieyi painting tradition, which placed emphasis on art that was about sensation, about emotional reactions, and the sentiments. This essence is perhaps captured in the idea that a ‘likeliness is spirit may reside in un-likeliness in appearance’ – i.e. not in a literal representation but instead in allusion, oblique reference or, to use the common catch-all word, ‘abstractions’ from a reality. If we look back into the conventions of Chinese painting, the tradition of abstracting, compressed viewpoints, changes of scale, stacked mountains, loosely-painted bamboo forests, and stylized clouds were all common, standing in as symbols that can be read in very different ways by different viewers. In the new invented universes that Ming Ren has created here in the early years of the 21st century, his intention is joined to the remarks made by the Chinese artist Gu Kaizhi some 1600 years ago “A painting should be somewhere between a likeness, and not”. The ‘abstraction’ also recalls the poignancy of poetry and it’s ability to distill complex emotions and storytelling into short concentrated bursts of words – or paint. In Chinese art traditions the boundary between painting and poetry is blurred – an old Sung Dynasty (c1100) saying tells that ‘Poetry is painting without form, while painting is poetry given form’.

Ming Ren has written that “We not only see with our eyes, but can dream and feel with our imaginations”. These joyous sensual works are the proof of that statement, and proof of his respectful connection back into several histories of art that have been platforms on which he has built a new and dramatic body of work. To do so he has become an explorer in new media, a magician working on a scale that invites problems, and has discovered destinations and solutions that were unexpected. To work like this involves considerable risk because the work has to succeed on an ambitious scale but not overwhelm – the delicacy of expression in the painted surface has to be maintained. To succeed you must have that streak of artistic bravery to tackle such problems. These paintings provide the evidence – Ming Ren is a brave man.

Tony Jones

Chancellor, The School of Art Institute of Chicago